the political brand

“The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway.

It's getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong

and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again.

That's how we know we're alive: we're wrong.

— American Pastoral, Philip Roth

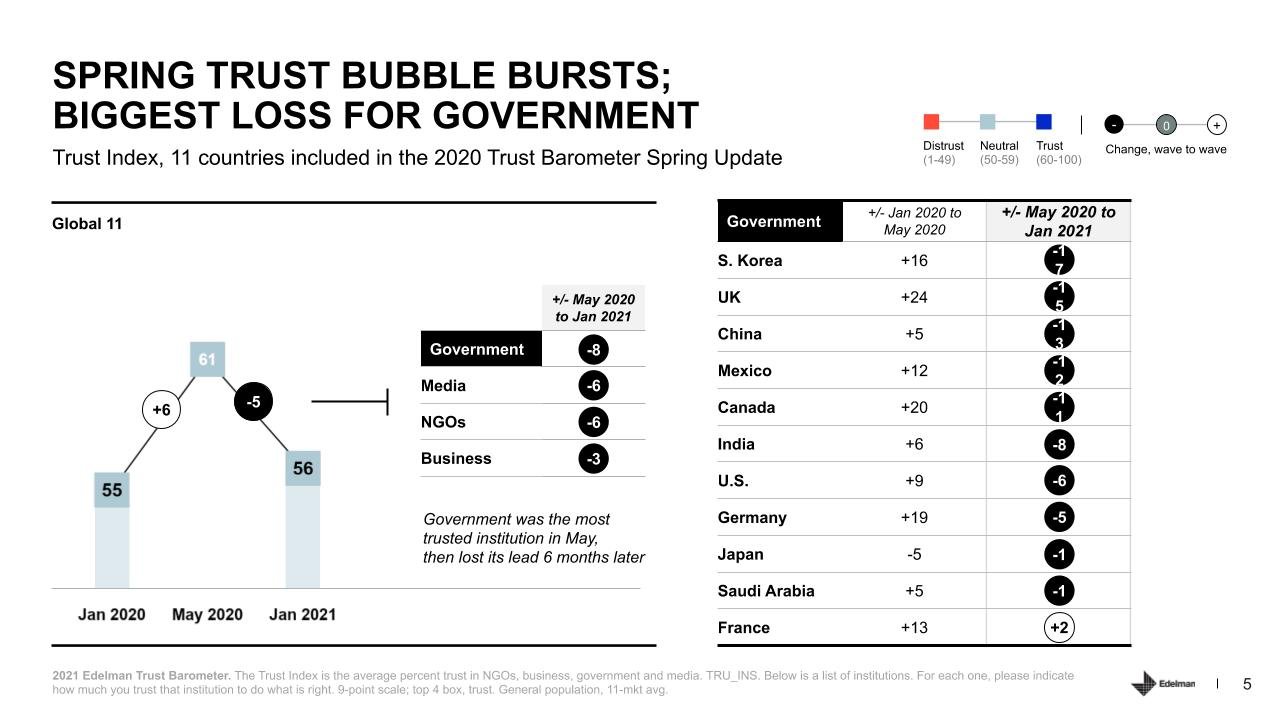

I honestly don’t know in what country you are reading this, but in general it really doesn’t look that good. Like literally anywhere. Politics doesn’t seem to be a thing anymore — at all. God knows how

we got here, but mistrust in our leaders has confirmed itself a worldwide trend. And the pandemic didn’t help.

“In power” and “in charge” have seemingly become horrendous phrases to indicate someone who illicitly occupies an arbitrary position. You don’t agree? Well, then ask yourself what political figures you personally trust in your own country. Count them, please. How many are there? One? More than five? I doubt that.

So, if we were to consider political parties as brands (which they actually are), then we would be looking at a huge problem, wouldn’t we?

We could call it a monumental drop in sales.

And perception.

And, of course, trust.

But let’s take it one step at a time. What does it really mean “to trust politics”? Arguably that we count on politicians to deliver in our best interest — for us and for everyone our community. We ideally confide in lawmakers to watch over us while we take care of our lives. It’s quite a service, isn’t it? And representative democracy doesn’t come away cheap: we literally give our leaders a very consistent part of our income, trusting that they’ll invest it in eventual necessities.

So, it feels like a set of responsibilities for which you really want to trust this kind of brand. We’re not talking about some shoe manufacturer, but a mix between a bank, your local police officer and a babysitter. You surely want to know them well before you entrust them with the life of your own kid.

There are of course many reasons for the current mistrust, starting from universally diffused cases of corruption, or generic disappointment (think about younger generations in relationship to climate change), not feeling represented due to a consistent age or gender gap, but also the sensation that politicians might have lost touch with the real everyday problems of average people. Isn’t this the ground on which populist movements have grown so strong?

I know what you’re thinking: “Right, this is where they tell us that we need a bit of human touch to make it all go away”. But I must disappoint you, because it’s not that easy. Not at all.

Enrico Cantoni, adjunct professor at the Department of Economics in Bologna University, and Vincent Pons, associate professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, have carried out research to:

“test whether politicians can use direct contact to reconnect with citizens, increase turnout, and win votes. During the 2014 Italian municipal elections, we randomly assigned 26,000 voters to receive visits from city council candidates, canvassers supporting the candidates' list, or to a control group. While canvassers’ visits increased turnout by 1.8 percentage points, candidates had no impact on participation. Candidates increased their own vote share in the precincts they canvassed, but only at the expense of other candidates on the list. This suggests that their failure to mobilize non-v

So, it is seemingly not just about human contact. Mistrust has rooted itself far deeper into our perception of politics than we thought.

***

In 1992 an American political scientist, Francis Fukuyama, wrote a worldwide bestselling essay called “The End of History and the Last Man”, in which he argued that with the fall of the Berlin Wall and therefore of the Soviet Union, we had come to an historical deadline of political conflict, since the world would slowly align to Western liberal democracy and there would be no more need for wars in the future. The Taliban, among many others, did not agree with this theory.

But what is unarguably correct about Fukuyama’s statement is that in the beginning of the 90s’ politics as we knew it had died. Globally shared values, political movements with millions of people asking for a better world, for universal peace, unanimous disarm, an overall fight against hunger and so on, those crusades led by charismatic leaders and political idols have vanished for good.

The spread of social media and technologies of intermediate connection have then given us the sensation that we could create relationships even more effectively worldwide through the screen of our smartphones. But is this really accurate? We surely possess a higher awareness of what is going on around the world, but are we really capable of feeling that direct connection with things taking place thousands of kilometres away from us? I’m talking about that kind of empathy narrated by Philip Roth in his masterpiece American Pastoral, where the young daughter of a middle-class couple decides to sacrifice her whole life after seeing Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc burning himself to death in Saigon.

We know more, but relate less, one could say.

And this is where political mistrust kicks in. Because politics is about relating to the needs of the communities. Having common issues at heart is the first step to a fulfilled voting conscience. Though if all the information we gather during the day (and it’s far too much) doesn’t lead us to action, then we don’t feel empowered to step in to what concerns shared necessities. And I’m not talking about citizens per se, but politicians mainly: we don’t think our leaders empathize enough with our needs. We feel their interest far too intermediate, their communication strictly tied to ulterior motives and more individual purposes.

The political brand has lost its capability of relating to the consumer’s wish.

But is there somewhere around the world a political brand that is trying hard to reconnect to their electoral basis? Of course there is.

“Women like me aren’t supposed to run for office. I wasn’t born to a wealthy or powerful family - my mother was from Puerto Rico and my dad from the South Bronx. I was born in a place where your zip code determines your destiny. My name is Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. I’m an educator, an organizer, a working-class New Yorker. I’ve worked with expectant mothers, I’ve waited tables, and led classrooms. Going into politics wasn't in the plan. But after 20 years of the same representation, we have to ask: Who has New York been changing for? Every day gets harder for working families like mine to get by. The rent gets higher, health care covers less, and our income stays the same. It’s clear that these changes haven’t been for us and we deserve a champion. It’s time to fight for a New York that working families can afford. That’s why I’m running for congress. This race is about people versus money. We’ve got people, they’ve got money. It’s time we acknowledge that not all Democrats are the same. That a Democrat that takes corporate money, profits off foreclosure, doesn’t live here, doesn’t send his kids to our schools, doesn’t drink our water or breathe our air cannot possibly represent us. (…)

We can do it now. It doesn’t take a hundred years to do this. It takes political courage. A New York for the many is possible. It’s time for one of us.”

AOC (as she is now famous world-wide) was born 1989 and took office in 2018, at the age of 29, winning the Democratic Party's primary election for New York's 14th congressional district, defeating Democratic Caucus Chair Joe Crowley — a 10-term incumbent. The quoted text you just read above is from the script of her campaign video, called “The Courage to Change”, written by AOC herself. It is a masterful example of both classical and emotionally impressive storytelling as we rarely have seen in recent years and we strongly recommend you to watch it.

Ocasio-Cortez is the youngest woman to ever serve in the United States Congress and, together with Rashida Tlaib, the first female member of the Democratic Socialists of America elected to serve in Congress.

Let’s run through some numbers. Twitter: 12,8 million followers. Facebook: 1,8 million followers. Instagram: 8,6 million followers. Makes your head spin, doesn’t it?

Between July 8 and 14, 2019, Alexandria drew more social media attention than the Democratic presidential candidates. Tracking company NewsWhip found that interactions with news articles on Ocasio-Cortez numbered 4.8 million, while no Democratic presidential candidate got more than 1.2 million.

Most of all, a corpse had risen from the dead: the Democratic Socialists of America.

Let’s put it this way: there is nothing scarier to Americans than Socialists (maybe only the Arab world is). The word alone makes the heart of the US tremble, making them instantly think about the end of the world as they know it: wealthy, capitalist and white. A fear still haunting them from the years-long struggle for supremacy during the Cold War. But it only gets worse for both redneck and super-rich America:

On February 7, 2019, Ocasio-Cortez submitted her first piece of legislation, the Green New Deal, to the House. She and Senator Ed Markey released a joint non-binding resolution laying out the main elements of a 10-year "economic mobilization" that would phase out fossil fuel use and overhaul the nation's infrastructure. In the process it aimed to create jobs and boost the economy. Ocasio-Cortez's environmental plan, termed the Green New Deal, advocates for the United States to transition to an electrical grid running on 100% renewable energy and to end the use of fossil fuels within ten years. The changes, estimated to cost roughly $2.5 trillion per year, would be financed in part by higher taxes on the wealthy.

Later in September, that same year, Antonio García Martínez of Wired opened an article stating: “I’LL JUST SAY it: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is a social media marketing genius, and very likely a harbinger of a new American political reality.”

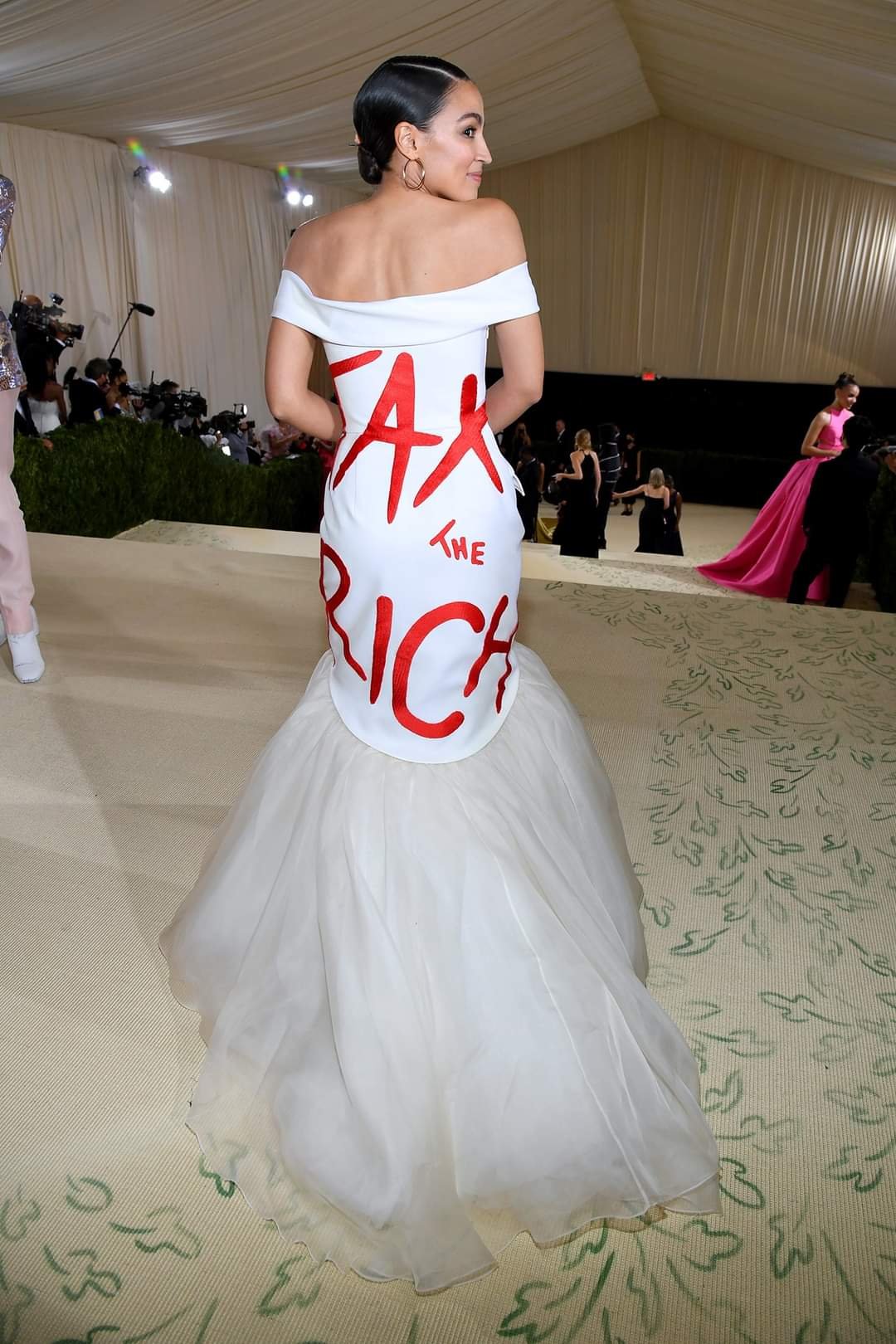

The leitmotif of raising taxes on America’s wealthiest then reached a highpoint in 2021, when Ocasio-Cortez attended the Met Gala, wearing an organza gown painted with the phrase "Tax the Rich”. This image of hers rapidly became top news in the whole Western world.

So, what we are looking at now is a very solid case of a brand that was perceived as old and obsolete, and that now has found a way to reconnect to its audiences. How?

First of all, by listening to their strongest demands: age and gender, two extremely delicate factors that have been connoted with the disconnection between citizens and politics. An aspect that was crucial in the evanescent capability to empathize with their representatives.

Secondly, communication: the old brand was connecting with its audience through outdated channels and with an old-fashioned tone of voice.

Third — showing the most human face they could get: humble origins, hardworking, unafraid of her fragilities (AOC has the great capability of showing herself both extremely determined and sometimes also crying live on her profiles) and most of all: optimistic towards the future.

Is it really that hard to imagine how good Socialism — such an outdated word, you could argue — is doing on social media? Well, at the dawn of the new decade, the hashtag #Socialism on TikTok got 345.5 million views, on Reddit inside r/socialism, almost 300k Comrades produce tonnes of content and information every day, while on all other social networks there are billions of interactions generated each year by profiles attributable to the struggles and campaigns promoted by the Democratic Socialists of America.

Hard to believe, right?

We are witnessing an exponential rise in loyalty towards activists rather than politicians and this is because the trending belief is that anyone can become an expert on anything by just googling stuff for half a day. Politics is a job, activism is not. And don’t get me wrong, I consider myself an activist, too; maybe more of an advocate, for certain values I believe in.

But this is exactly the point: nowadays everybody likes to consider themselves activists for something, because it just takes a bit of time during each day, taking a break from posting pictures from our parties and pets, to repost some superficial opinions about climate change, to make us activists.

Though the big difference is this: activists point out a problem that politicians will then try to solve.

It’s too easy for some media to say “Greta Thunberg is just complaining about things without suggesting any solutions”; it’s not her goddamn job! She is a kid rightfully concerned with climate change, the ones handing out solutions should be the politicians!

When we entrust activists with our loyalty, we are practically patting ourselves on the shoulder. And this kind of individualistic approach is key to understanding the mistrust towards politics.

Brand Loyalty means that I as a consumer trust a certain message over a longer period of time, because I confide that the brand won’t let me down, nor betray my expectations.

The lesson marketers and brands have to learn from the political brands and specifically from the Democratic Socialists of America, is a key driver for radical change: you really need to start listening to your audiences and act accordingly. Not only: it is urgent that we begin to form a stronger empathic connection with consumers, putting on a human face, more similar to their own, showing feelings they can relate to, contributing actively and concretely to an improvement of their lives. Otherwise, we will lose them; and lose them means chaos in terms of political mistrust and bankruptcy in terms of entrepreneurship.

Brands really could help make this world a better place, but there is one required factor they cannot ignore: they need to want it, with all their hearts. But they need a heart first. Logos don’t have a heart. People do.

first appeared on Human Brands Observatory on November 27th 2021

all rights reserved no panic srl ©